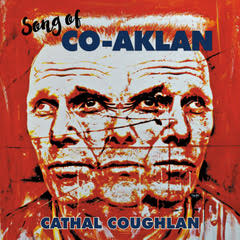

Cathal Coughlan has with a new album, the brilliant ‘Song of Co-Aklan’, his first in ten years. Seamlessly blending his lyrical prowess with fine indie melodies, the former Fatima Mansions and Microdisney man has returned with possibly his greatest work yet. We caught up with him to find out what’s behind the making of one of the albums of the year:

Cathal Coughlan has with a new album, the brilliant ‘Song of Co-Aklan’, his first in ten years. Seamlessly blending his lyrical prowess with fine indie melodies, the former Fatima Mansions and Microdisney man has returned with possibly his greatest work yet. We caught up with him to find out what’s behind the making of one of the albums of the year:

It’s been ten years since your last solo album, why was there such a long gap?

Real life’s interventions, for the most part. Not being a massive commercial success in music makes these kinds of breaks inevitable. I was lucky, though, in having a flow of live performance projects which kept me occupied and focused on my voice and other skills, using the time available. Ultimately, it was the cumulative effect of these which led me back to recording.

I can hear events of more theatrically based music within the album, were you listening to more non-rock based music, and if so what were you listening to?

One accidentally great thing about the 1990’s, for me – and believe me, I do realise what a huge time has passed since then – was that the various tawdry cultural events which occurred (take Britpop, for instance) made it abundantly clear to me that rock music was never again going to turn on its axis around the works of culturally-engaged and imaginative individuals like David Bowie or Prince. It was going to descend into genre segmentation, with a big emphasis on craft and homage, which are ok in their way, but can make for dreary work.

So I began seeking the inspiration needed to continue producing work from a wider universe of music. Anything from unaccompanied Irish language singing, to the folk and popular music of Asia Minor (rebetika, Turkish song, etc.), to French pop, old & new, free improvisation or the avant-garde end of hiphop. And so it’s continued, for me. Over the recent several years, I’ve devoted a lot of time to immersion in the songs composed by & for the works of Bertolt Brecht, by the composers Kurt Weill, Paul Dessau and Hanns Eisler. I truly believe that this is where punk meets the conservatoire, and it predates anything the 21st century corporate establishment cares to suborn, in the way that it has so many other styles of popular music.

The title of Co Aklan seems a mythical place, what does it represent to you?

Well, it’s more of a mythical person rather than place, to be honest. After so long away from releasing music, I felt like someone with nothing to lose, including past identity (the warm reception accorded to the album has been a surprise). So I decided to begin moving my external presence towards this re-branded, de-racialised entity, who can act as a kind of green-screen for whatever avaricious, comic or pretentious intent needs to be unleashed on the public.

Up to now, I think it’s going well, and new phases of the entity’s evolution will be conceived & announced in due course. It kind of puts me in the headspace pioneered by the ever-rebranding, ever-crap P. Diddy, but on a micro-budget, which simply feels right. A guiding ethos, however ridiculous, can lend purpose and cause useful collisions.

On the new album, you’ve worked with a lot of amazing musicians including your band mates in Microdisney and Fatima Mansions, how did you decide who to collaborate with for this album?

It was a bit of a struggle, to be honest, because I didn’t want to seem to shun the skills of anyone, especially not the quartet who played with me throughout the 2000’s. But the (I fancied) artistically successful elements of the material I came up with, leading up to 2019, demanded certain things, such as electric bass guitar and electronic keyboards – which had been largely absent from my records for a lifetime or more. I’m lucky enough to know quite a few very talented players, and to have encountered a good cross-section of them in 2018/19 (when doing my own shows and the Microdisney reunion shows), so it just went from there.

On the title track there’s the phrase “blame the unwanted” the song seems to be about feeling lost in this culture of consumerism, and social media, is that what was in your mind as you were writing this one?

I was describing the licence which is being given to the public, from the Right (which is – sorry to say it – still a real and a growing thing, undimmed by globalisation and consumer culture), to ‘punch downwards’ in response to the dispossession (usually meaning declining living standards and lack of access to housing and other basics) and the constant sense of crisis which they are experiencing. Mainly as the result of the financial, media and political machinations of that same Right.

This means that populations which consider themselves ‘native’ are encouraged to use their voices to deride, terrify or repel any neighbours who don’t fit the nativist bill. That usually means migrants, but of course it’s widening out, now, to cover those who can be identified by lifestyle, cultural interests, educational background, etc.

‘St Wellbeing Axe’ is one of my favourite songs on the album, and has the guitars and menacing bass working well with the foreboding lyrics ‘the dim star liner is boarding in the city’, is it about trying to get people to be more kind to each other, and have more tolerance?

‘St Wellbeing Axe’ is one of my favourite songs on the album, and has the guitars and menacing bass working well with the foreboding lyrics ‘the dim star liner is boarding in the city’, is it about trying to get people to be more kind to each other, and have more tolerance?

I wish! I think the message you describe is present in a lot of my other work, but this song is more complicated and sees the world from the viewpoint of a person whose world is being dragged off-balance by their poor physical health. There are places in the world – and, as yet, relatively few of them are in the UK, but this could change – where becoming ill is a one-way ticket to a world of degradation and constant worry, about the competence and cost of the care a person suddenly finds that they need. So, in the song, the authorities have literally moored a hospital ship in the city and made that to serve as a place to which all & sundry of the ill population must go, to have the worst news of their lives, in many cases.

But I’m not aiming for agit-prop of any kind here, not least because the other thing I believe is that, even in places where illness all too easily becomes a multi-faceted nightmare, at the core of it, there are professionals who are just trying to help others, the best they can. Without such people, the world can’t function, and they’re all too often unrewarded, or treated as ‘the problem’.

I’m just trying to get inside the skin of a typical seriously-ill person, as they contemplate their situation, and where it may lead. They see themselves as the victim of some horrible unfolding existential joke, and they don’t take it well.

Was this album already written pre pandemic or did you find the global situation fed into your album writing process?

It was already written, but quite a lot of it, including many vocals, where recorded in the first 5 months of the pandemic, so the echoes were profound. It’s impossible to feel gratified by that immediacy of resonance, though, when people are dying unnecessarily, “piled up in their thousands” (to coin a phrase), or are about to become impoverished, in considerable part as the result of some of the negative human traits I was describing in songs, as manifested in the populist-political world.

How have you coped during the last year, what has kept your spirits up through these challenging times?

Hard to say, really, as even the societal average for spirit levels has been very, very low. The main things which have kept my spirits up has been making music in a couple of different roles, and keeping my body as exercised as possible. I wish I could say that my reading and viewing had been illuminating, but I’ve merely been hogging the default subsistence level in those things. A lot of music has inspired me, especially Linda Buckley’s album From Ocean’s Floor, which just keeps giving. The new Luke Haines album is very fine, also.

You are, in our opinion, one of the best lyricists around, but who do you think are the finest lyric writers either living or historically and why?

Why, thank you!

For sheer brazenness, it’s impossible to equal Bob Dylan, in that he’s able to fasten onto what can most charitably be termed ‘found’ source materials, and mutate them only slightly, to produce a total transformation and an enveloping sense of the uncanny. If that makes me a dad-rocker, so be it. I love many songs by Peter Blegvad, which achieve a similar effect by more original means.

I love and hugely enjoy the work Graham Lewis has done in Wire, over the many years they’ve been active, and not a million miles from that style, nowadays Elizabeth Bernholz a.k.a. Gazelle Twin, King Krule and Daniel O’Sullivan. Texan singer-songwriters like Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark were unbeatable at what they did – true gravity, married to a common touch. There’s great common touch, too, in Paddy McAloon’s work, and optimism about human nature, expressed with great elegance. My friend Luke Haines is really, really good – funny, and nonchalantly time/space-bending (e.g. Lenny Valentino and many more). There’s no bias in my saying that.

I admire those who can turn time and reality on their heads and produce something which, while it would never work purely as poetry, sparks magic inside of a song. This can sometimes just be through a core of raw human feeling which emerges amid seemingly youth-specific commercial pop music – say, in the words Bob Crewe & Bob Gaudio wrote for Frankie Valli & the Four Seasons, Holland-Dozier-Holland, Norman Whitfield and Ashford & Simpson at Motown, or Dan Penn & Spooner Oldham.

And of course I love Scott Walker, who just got better and better as he got older, right to the end. Joni Mitchell, too, and Annette Peacock. Bryan Ferry was an amazing lyricist, until (I imagine) life brought him many of the rewards whose absence had powered his imagination. Nick Cave is someone whom I respect, and he can be a truly great classic lyricist, or great gutter lyricist, on occasion. Richard Thompson has a large library of classics, which is still expanding.

That said, I don’t tend to listen to song words with great alertness – fact!

Nowhere else in the business of making music is it more often the case that a person making work for their first time ever, in this case the words of a song, can wipe the floor with veteran craftspeople. And perhaps never do anything that good, ever again. Ditto for the for-hire mechanic who usually just decants copping-off doggerel out of their rhyming dictionary, but hits a real vein here and there.

It’s at once both part of the vitality and the cruelty (to its practitioners) of pop music that the concept of a ‘canon’ is not so fixed that, as in other genres of music, it’s decreed that the lyricist or composer is either ‘on the pantheon’, which is the only location where the work can be appreciated, or somewhere out in the interplanetary void, where the work effectively never existed. There’s not really a pantheon, which can make for tough let-downs.

Words and stories are just part of our makeup as humans. There should be, and sometimes is, no craft at all to making them into songs. And, let’s not forget, so much that is great has come from traditional sources, with no author credited at all – think St James Infirmary, Last Kind Word Blues, Henry Lee, Katie Cruel…the list is literally endless, we only know a part of it.

You seem to be constantly challenging yourself, as well as this album, you have an album in the pipeline with Jacknife Lee, what’s next for you this year, touring or more songwriting?

Yes, the first of what we expect to be a series of albums from Telefís, the project around Jacknife and myself, will begin surfacing in early summer this year. We’ve begun work on the second album, and I’m also writing towards the next Co-Aklan record, although it’s early days for both. I wish playing live were could just be the reflex it was up to recently, but at this point, in part due to my own situation, I don’t know when it will be possible. The reception for Song of Co-Aklan has arrived at pretty close quarters, due to social media, and that’s given me some perspectives on my back catalogue which I don’t know whether I would have had, otherwise. I’m looking forward to putting some or all of those into practice through a live set, as soon as it’s practical to play for people.

Song of Co-Aklan is out now. Check www.cathalcoughlan.com for tour details.