Sean Pecknold is a director and visual artist from Seattle, now based in Los Angeles. Starting out in stop-motion, the multi-dimensions artist has spent a life-time expanding his poignant perspective – letting the colours of his understated world run from rich animation into grand, live-action. Here, he speaks to his beginnings in videography, how geography has affected his work and demystifies his collaborative relationship with brother and Fleet Fox Robin Pecknold.

How did your relationship with videography begin?

My first job in Seattle was working the Kiss-Camera at the Seattle Marinerʼs stadium Safeco field. My Dad was a title designer and film editor when I was growing up and taught me the fundamentals of design and editing, and would bring home music-videos that heʼd been cutting and I remember being fascinated by the process. I was lucky enough to get one of his old laptops when I was 18 and he had a program called Avid Express on it, and I would cut little short films and videos in my spare time outside of school.

After graduation, I spent a lot of time getting more into photography. I shot live-music photography at Seattleʼs Bumbershoot and Sasquatch Festival for a few years, and was also teaching myself digital animation – trying to figure out where my talents fit best. When my brother first started Fleet Foxes, thatʼs when my interest in photography shifted towards stop-motion animation and I was able to dive into a pretty ambitious music video for their first single ‘White Winter Hymnal’.

With sketching and photography, it’s easy to see that your talents aren’t limited to film. Can you speak to any experiences that propelled your focus on stop-motion and video?

When I was living in Seattle, I was working as a full-time editor at a post-production company – working on documentary content, and as the days would drift by I would find myself wanting to be outside shooting the stuff that I was editing. An opportunity arose one summer to make a short film for a 48-Hour Film-Festival, and it coincided with me handing in my 2-week notice at work. Myself and my friend Matt Daniels did a short that was basically stop-motion, or Pixelation as itʼs often called, where you shoot with humans instead of puppets. It was narrated by our French friend Elsa, and was about a small boy who loses his bike. We ended up winning the competition, and thatʼs when I was sure that I wanted to pursue direction and animation.

I found it very fun to shoot multiple photographs together to tell a story, and although I didnʼt really have a traditional education in animation, I was fairly comfortable teaching myself as I went along. On the first Fleet Foxes video I did, I was lucky to have some very talented animators in Britta Johnson and Chris Rodgers to help me out and I learned a lot about the technique and process. Around the time of the second Fleet Foxes video I did for the song ‘Mykonos’, I experimented with paper stop-motion animation, and it was my first time trying this program called Dragonframe, which has since become my go-to program, and that really helped me become a better animator.

Though I always knew that I wanted to make videos and films, I pursued animation because it allowed me to make something pretty large-scale on a limited budget. I could literally think of anything and find a way to make it with just a couple of other friends in a dark room. I didnʼt want to limit myself to just animation though, and since moving to LA have been working a lot in live-action. So now, when Iʼm thinking of what I want to make, it can either be animation or live-action, it just depends on what it is, and what I want it to be. Itʼs been fun to delve deeper into working with actors and more crew and to try and make films to the scale of some of my previous animation work.

Did growing up in Seattle influence your visual pallet, and did those influences shift when you moved to Los Angeles?

I think being in the northwest affected my visual palette. I tend to like moodier colours and tones that are reflective of the greys, and blues, and greens up there. I think mountains tend to find a way into my work in most projects – animation or live-action. We grew up just outside of Seattle, looking east at the Cascade Range, and west to the Olympic Range, and they were always there looking down on us. The other thing about the Northwest was it was often grey for 9-10 months at a time, which actually lends itself well to staying inside and making things. I think thatʼs why it is a fertile place for music and art; there isnʼt really much to do there. The long winter stretches of grey force you to pick a craft or focus that you can do inside. My brother chose song-writing and music and I chose film and animation.

Since moving to Los Angeles a few years ago, I think my visual palette has expanded a bit. It took me a while to get used to so much sunshine, itʼs like the exact opposite problem of the Northwest, and can be quite tough to endure in the same way that constant grey and rain is. The sun can beat down on you so hard that itʼs impossible to think or work sometimes. But there are still some mountains and forests real close-by that have been very important over the last couple years.

Sometimes you really have to search for new visual inspiration in LA. All the old signs and painted buildings and typography that line the streets here are pretty inspiring. I spend most days in Chinatown where I have a small studio with Adi Goodrich, my creative partner, and weʼre really inspired by the color palette of the buildings and shops. Itʼs the kind of city that rewards the people who scratch underneath the surface to find the hidden gems. Just last weekend Adi and I were exploring the museum at the Forest Lawn Cemetery grounds, and stumbled upon the most incredible painting weʼve ever seen, The Crucifixion by the Polish painter Jan Styka, I think it’s one of the biggest paintings in the world. Itʼs quite awe-inspiring.

Your videography always seems to hold an element of philosophical questioning or struggle. Do these ideas commonly shape the foundations of your films?

For me, itʼs not necessarily “I must add some philosophical questioning to this piece”, I think itʼs just a natural extension of who I am, and how I try to reflect the world I see or the questions I have at the time. Often I think of things first physically, such as, whatʼs the movement in this film, what is the build-up and tension in the animation or the dancing or the story, and then I try and discover what question Iʼm trying to explore with it. Itʼs more fun, and I think more fruitful, for me to attach my questions to someone else, be it human, animal, or a simple shape, and see what they discover along the way of whatever journey I set them on.

Can you speak to the relationship between your works and your brother’s music? Have they always influenced one another?

Itʼs very important to me, because heʼs still my biggest inspiration. We started to get into music and film around the same time, though Iʼm older than he is. His music has always inspired me to make work better and bigger. Because we grew up watching the same TV shows and movies, and we still do, I think we have a good short-hand language when talking about inspiration for collaborative work.

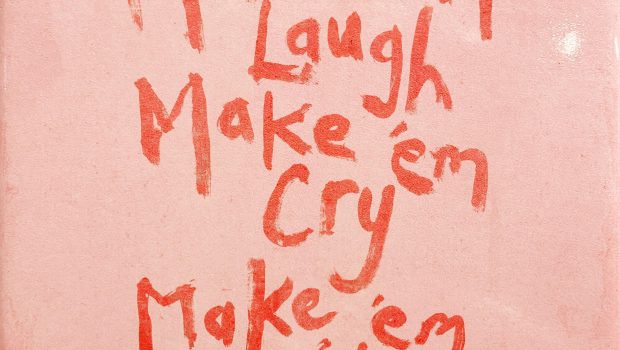

I think Iʼve been a bit spoiled making visuals for Fleet Foxes songs, as they have an inherent cinematic quality to them that lends well to both animation and film. The songs are rich and full and have a lot of dynamic movement and unexpected changes that make for interesting opportunities to visualize.

The new record ‘Crack-Up’ is full of rich textural sounds, instrumentation and unexpected shifts in tone and flow. To me, it sounds like something new – a big step forward. Iʼm really excited about getting the chance to visualize some more tracks very soon.

Whatʼs next for you?

I’ll be working on a feature film in the next year, a handful of other music videos, and I run a studio in Los Angeles with Adi called Sing-Sing, where we do a handful of visual projects together. Exciting things on the horizon!

SEAN PECKNOLD Official | Vimeo | Twitter