-MANCHESTER ARENA-

There’s a part near the beginning of the recent Nick Cave documentary, which charts the making of Skeleton Tree, his latest album with the Bad Seeds, in which he says:

“Isn’t it the invisible things, the lost things, that have so much mass? And are as big as the universe?”

Cave has recently suffered a terrible loss – his son died in a tragic accident during the recording of the album. He later said of the film, “it gave Arthur’s absence, his silence, a voice”. The accident itself is rarely mentioned directly in the film, but it has so much mass. I’m on my way to see Nick Cave play at the Manchester Arena, listening to the album as I walk, and so much of the recording is heartbreaking. I know that when I leave the gig, I will have to write about what I see there, and I think to myself – is it appropriate to mention this loss? Is that tabloid and crass, or is there a respectful way to do this? But then, the opposite question comes to me – is it possible to experience this concert without thinking about this loss when it does have so much mass? An elephant in the room as big as the universe? I recently read an article about emotion in opera performance, in which the writer says:

“I’ll never forget an opera coach’s advice to me. He said something like, ‘You just cannot expect a singer to go night after night giving everything to the music. It’s not physically possible. […] You want a good show? Well, if the singer loses their voice, which they will if they disregard technique to “feel” or “let go” onstage, then there won’t be a show to judge.’ And he’s absolutely right.”

Opera is a physically demanding medium. Similarly, Cave’s performances are famously visceral and physical. So many of the lyrics on the album – mostly written before the loss – seem to refer to Cave’s personal trauma directly. The idea of doing something so physically exhausting, and at the same time facing something so emotionally exhausting head on, sounds impossible.

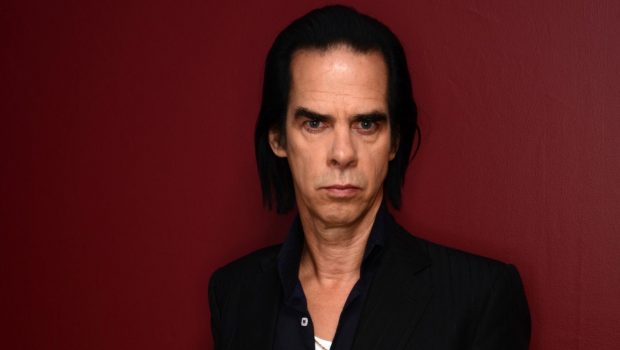

Nick Cave enters the stage at the same time as I enter Manchester Arena. He looks much calmer than I do. Security has increased in recent months, and they didn’t let me in with a rucksack. By the time I’ve run to North Manchester to leave it with a friend who’s working late, then back to the arena, up the stairs and into the space, I’m out of breath. I watch as he walks to the middle of the stage and sits on a stool, completely collected. The crowd screams, and the band starts. Somebody shouts “we fucking love you!” and he replies, “well I’m glad we got that straight.’ He begins to sing, and I’m surprised despite myself that his voice is as thick and dark and faultless as it is on record.

“All the fine winds gone,

And this sweet world is so much older”

Cave looks oddly alone for a man with so much presence, with a sizeable rock band behind him and a whole stadium full of people there to see him. He is set quite apart from his band, just about the same distance from them as he is the audience. He gets up and walks forward.

“It’s a long way back, and I’m begging you please to come home now.”

The audience is covered in purple and blue light, and a white light which pulses with every bass guitar note. Between him and them is a 3-foot trench in which security and stage attendants stand, and on the crowd’s side of this gap, three podiums. Cave leaps over this gap onto a podium and reaches out over the crowd, who reach up to him in a way I’ve only seen before in zombie films, grasping at his white shirt and black suit. He beckons to the crowd further back to come forward, and the whole of the standing area of the arena surges forward in a wave. “That is Biblical, that,” a woman sitting behind me says.

“Come as far as the edge of my blood.”

And Biblical is exactly how it feels – I am awed throughout the gig at the complete control Cave has over his audience.

“Now swim.”

The stage lighting turns blood red for ‘Higgs Boson Blues’, the first song in the set that doesn’t come from the latest album.

“Can you feel my heart beat?”

He jumps backwards and forwards from the stage to the podiums throughout the gig. Much of the time it feels like he’s more part of the audience than the band. I wonder what would happen if he fell. But he is absolutely collected – to put a foot out of place feels like it would be out of character. From one of the podiums, he pushes his chest out to the audience so the front row can try their best to feel his heartbeat. For the benefit of the rest of the room, he tells us what it feels like, a line that isn’t on the record.

“It’s going boom, boom boom.”

It feels, watching, like he is trying to share something with the room. It’s an easy comparison to make, given the fire and brimstone delivery of many of the Bad Seeds’ songs, and the religious references in so many of the lyrics, but it feels exactly like I’m watching an evangelical preacher in a film or a documentary. It feels like there is some kind of mystery that he alone knows and he’s trying to share it with the audience through his performance, and the grasping hands on the front row are desperate to receive it. He waves to the band to quieten the music down and speaks out to a person in the crowd.

“About the socks?”

The audience member he’s addressing has evidently annoyed him by shouting too much about the purple socks he’s wearing.

“Yeah I know, we get that though. Yeah I know, but it’s really distracting. You finished with that?”

The band continues to loop the song behind him.

“It’s okay. I mean, freedom of speech and all of that, but shut the fuck up.”

The crowd roars with approval. The song continues. Near the end it becomes clear some kind of incident is happening in the middle of the crowd. A group is shouting out Cave for help.

“What?

I don’t know what you’re saying.”

For a minute things feel very tense. He eventually gets the message that somebody needs first aid.

“Shut it down,” he tells the band.

“We need some help.”

The band stop playing, and I watch as first aid pushes through to the middle of the crowd while the band launch into the next song. I look away from the stage during the following song as they return with a man looking worse for wear. When I look back at the stage, there is a boy who looks about twelve next to Cave, wearing a Bad Seeds t-shirt. “The little children know”, Cave is singing, and again I have the feeling that something supernatural is happening in front of me.

“I’m transforming, I’m vibrating, look at me now.”

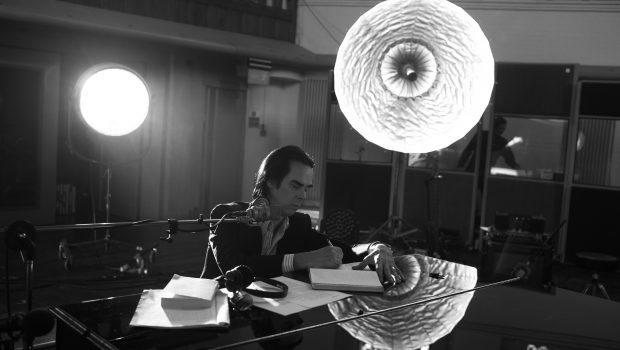

He throws his microphone across the stage in a way that might have looked like a petulant wannabe punk gesture on anyone else, and sits at the piano. When the camera zooms in on the side of the piano, I can see a piece of fabric hanging down with the words ‘SMOKING, MELTING, BOILING, BURNING’ sewn onto it, words from Cave’s song sung from the point of view of a man in the electric chair, ‘The Mercy Seat’.

But now things become a little lighter as he begins ‘The Ship Song’. The mood is suddenly joyous, and Cave looks so authentically happy as the crowd sing along. At the bottom of the seated area a couple are slow dancing. “It’s a privilege for us all to be here,” he tells the crowd after the song, and then begins to sing ‘Into My Arms’, another soothing, piano-led ballad.

“And I don’t believe in the existence of angels. But looking at you I wonder if that’s true.”

This new mood is just as natural as the violence and noise that has characterised much of the set so far. “Thank you very much,” he says to the crowd. “You have no idea.” Cave returns after this piano ballad interlude, to songs from Skeleton Tree.

“I used to think that when you died, you kind of wandered the world in a slumber till you crumbled, were absorbed into the earth. Well, I don’t think that any more.”

There is a woman on the edge of the crowd, metres away from where the couple were dancing before, with her hand in the air, and her head bowed, shaking violently in a way that isn’t related to the tempo of the music at all. It looks exactly like videos I’ve seen from evangelical churches, of congregation members moved by some higher power.

“‘Cause nothing really matters when you’re gone.”

The emotion in these lines feels so direct and palpable.

“I’ll miss you when you’re gone away forever.”

He is asking the audience to sing the words for him, “just breathe, just breathe, just breathe.” These last songs, which close Skeleton Tree, are some of the most affecting, and feel like a release of all the heartbreak and tension that have come before.

“And it’s alright now.

And it’s alright now.

And it’s alright now.”

In the documentary One More Time With Feeling, Cave suggests, discussing his music, “Maybe songs serve a certain need.” The band begin their encore with ‘Weeping Song’, the chorus of which tells the audience, “this is a weeping song, a song in which to weep.” Through the set I’ve been struck by the degree to which Cave is sharing such intense emotions with the audience – emotions of all kinds – and wondered what everyone was getting out of this. It doesn’t feel, when the audience are grasping up at Cave, like they’re doing it for the sake of touching a rock star (or just for this reason). It’s like they want something from him, and the songs are serving a certain need – these are songs in which to weep, for Cave and for the audience, as well as songs in which to feel all the different emotions Cave completely embodies, from anger to joy to sadness. Like a preacher promises their crowd knowledge of the divine that the preacher alone has access to, it feels like what the audience get from Cave is some kind of deeper knowledge of these emotions, which he has experience intensely and deeply, and the songs are a vehicle in which they can do that.

Cave is walking towards my side of the arena. He jumps off the stage and comes to the bottom of the stairs on my block. People behind me are walking down the steps, trying to get closer to him. I start walking down too. For all my overthinking the dynamic between Cave and the crowd, I’m not immune to it – the idea of being close enough to the man that’s been holding an entire arena captive since the beginning of the concert is hypnotising. I don’t get there nearly in time, and instead take another seat closer to the stage. From here I have a close-up view of another moment that seems purely supernatural – Cave pulls around fifty audience members onto the stage with him, including the boy from earlier, and for a while I can’t make out where Cave is in the crowd on stage, and realise the boy is holding the microphone and has taken over the vocals to Stagger Lee (only the “yeah yeah yeah” bit, although he has been mouthing all the other extremely not-PG words). Cave asks all the audience members on stage to sit on the floor for the last song, ‘Push The Sky Away’. They all sing along while looking up at him adoringly like a chapel choir.

“And if you feel you got everything you came for,

If you got everything and you don’t want no more,

You’ve gotta just keep on pushing

Push the sky away.”

Maybe performing such a physically and emotionally exhausting show would be too much for us mortals, but I have never felt more like something supernatural is happening in front of me. So many audience members looked throughout this concert like they were experiencing something completely cathartic and significant for them on a deep emotional level, and it felt like Cave did too. When he thanks the audience, tells them how much being there means to him, and that they have “no idea”, it all feels like he really means it, and the experience has been as cathartic for him as the audience. I hope so.

Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds: Official | Facebook | Twitter