Soup Kitchen has announced a show for songwriter and solo artist Willis Earl Beal. Details of the show are below…

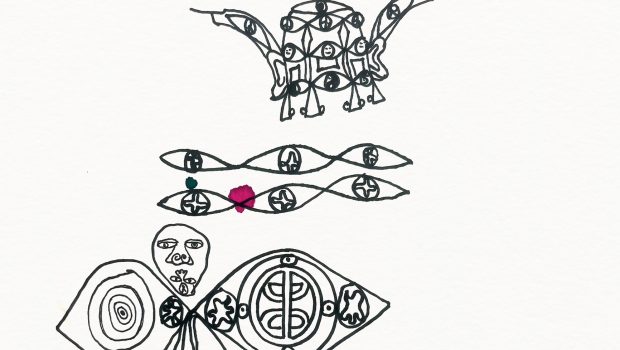

Willis Earl Beal was born on the South Side of Chicago. He would never consider it home. An odd kid, he spent a lot of his youth talking with his grandmother, who would entertain his endless questions about the universe and encourage his love of drawing. He developed an obsession with Batman that would last well into his teenage years, when he enlisted in the U.S. Army as a form of vigilante training.

Willis Earl Beal died on an army base in Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. After a rocky TK weeks of boot camp plagued with physical and mental abuse, health complications (which would later require surgery and the removal of large portions of his intestine) forced his discharge. He moved back home. “When that all broke down,” Beal says. “I lost a piece of myself.”

Willis Earl Beal was born in Albuquerque, New Mexico. After a stint of homelessness there, he worked odd jobs and rented a studio apartment. Though he’d never learned to play any instruments, he began to record raw, lo-fi albums with hand-drawn covers that he’d leave at coffee shops around town alongside flyers seeking a girlfriend with his phone number written on them. Those artifacts would eventually find their way to the cover of Found magazine, then to Jamie-James Medina at XL Recordings. Beal signed with XL’s Hot Charity imprint in 2012.

Willis Earl Beal died in New York City. Despite the release of two critically well-received albums on XL-Acousmatic Sorcery, a collection of his early home recordings, and a fully orchestrated studio album he recorded in Amsterdam called Nobody Knows-he was a mess. “I’d drink myself into stupors,” he says. “I’d walk around in the daytime, crying, then I’d go downtown. The police would bring me home in the morning.”

Willis Earl Beal was born on a lake twenty miles outside Olympia, Washington. After ending his contract with XL, Beal went to live in the woods, and began an artistic transformation entirely of his own design, from rough-edged outsider-art provocateur to the kind of mysterious crooner one might expect to haunt the outskirts of Twin Peaks. “People had all these ideas about what I was supposed to be,” he says. “I had only ever wanted to make lullabies.” Beal’s development played out over two self-released EPs and a full-length album, and then Beal built the patient, ambient-leaning Noctunes. The album’s twelve songs are moving and meditative, thoroughly soaked with mournful synth strings and simple lyricism that Beal says is intentionally minimalistic. “I wanted to create this persona that could say everything perfectly with very little,” Beal says. “The record, to me, is a perfect record. I listen to that thing a lot, and it helps me.”

Willis Earl Beal has yet to be born. Critics and publicists defined him before he’d had a chance to define himself. Their expectations were inextricably linked with race and gender, two concepts Beal thoroughly rejects. Now, two extremely productive years removed from the spotlight, Beal doesn’t feel pressure to define himself against anything. His new music is shockingly original, utterly confident, and as ephemeral as Beal himself. He levitates above definition, concerned only with self-discovery and truth-seeking. “I know it sounds falsely altruistic,” he says. “But I think a simple voice like mine can serve as an example of some kind of freedom.”