-APOLLO, MANCHESTER-

Annie Clark (stage name St. Vincent) told Pitchfork earlier this month:

“All human beings create their own mythologies, and I’m in the somewhat bizarre circumstance of creating a big mythology that gets shared with a lot of people. In some ways, doing the work that I do is about reinventing a value system. More or less, there’s a ubiquitous value system in America, these markers that signify your rite of passage into adulthood or into validity: getting married and having kids and having mortgages. But I always felt a little bit like an alien cocking my head to the side at various cultural milestones, going, “I would never aspire to that.”

Last night I went to watch Blade Runner 2049. I know this isn’t a film review website, but bear with me (if you don’t want Blade Runner spoilers, or don’t want to read about violence against women on film, I’d skip forward four paragraphs).

I hadn’t been to see a film in the cinema since the film industry’s endemic and horrific sexual harassment problem came to light, most prominently the exposure of film producer Harvey Weinstein as having sexually assaulted many of the women he worked with. The film is stunning from a cinematography perspective, and has been reviewed very, very positively. But after what has come to light about Harvey Weinstein, and how the film industry works – powerful men abusing their power, women expected to accept that abuse as part of the job, cast and crew expected to look the other way – the thing that really jumped out at me about the new Blade Runner film was how the women and men in the film are treated and represented. The film is full of gratuitous violence against women. The only time two women in the film talk to each other about something that isn’t a man is very briefly during a scene in which one of them goes to talk to another about a man, on the orders of a man, and then one woman kills the other.

To quote Sara Stewart, “Female characters get the short end of the stick in this long-awaited dystopian sequel; they are drowned, knifed in the stomach, shot point-blank in the head and, in one instance, simply winked out of existence with the stomp of a boot. All, it must be said, with artful cinematic relish.” Jared Leto, playing the owner of a company which manufactures clones, gets the award for most unnecessary gratuitous violence – after some laughable dialogue between him and his maid in which he compares himself to God the creator, he is led to see the latest (female) model of clone, which slips nude from a womb-like sac on the ceiling. Leto wishes the clone happy birthday, kills her, then kisses her on the lips. Many scenes are dominated by huge naked statues, or holograms of women.

The women in this film exist to do things for men, look good for men, and carry out men’s orders, and then half of them die gruesome deaths. What this film says to women is, “in the future, you will exist to do things for men (in real or hologram form), carry out the orders of men, and then die gruesome deaths”. What this film says to men is “in the future, you will be brooding, chiselled, very important, punch first and ask questions later (the first thing our two heroes Ryan Gosling and Harrison Ford do when they meet is have an extremely macho fight, while holograms of Elvis and Marilyn Monroe flicker in and out of focus behind them), and women are there for you to order around, ogle or have sex with”. What this film says to LGBTQ people is “you don’t exist” and what it says to people of colour is “you only exist as bit-parts in a bigger story” (and in the case of Asian people, “you exist as an easy way for us to let the audience know we’re in ‘the future’, but not on screen at all”). What it says to disabled people is “you don’t exist, oh no wait Jared Leto’s character is blind but only as a quick way for us to signal to the audience that he’s a bit creepy and evil”.

Is there anything in the film that might give us hints as to how we might avoid this future? Or even that there’s anything wrong with these things? Not that I could see. The presence of hyper-feminine and hyper-masculine icons Marilyn Monroe and Elvis are the only indication the film might have any self-awareness when it comes to gender. As Devon Maloney says, “Several moments almost comment meaningfully on women’s disposability—Wallace’s casual gutting of a newborn female replicant; a giant, naked Joi addressing K blankly from an ad—yet each time, they become sad moments in a man’s narrative, rather than being recognized as tragedies for the women themselves.”

Blade Runner doesn’t have anything to say about misogyny apart from, “Sorry everyone, in the future there will still be misogyny. It’ll mostly be exactly the same. But it will be different, because it’ll be set in the future. Future misogyny.” All human beings create their own mythologies, but these mythologies shape how we understand the world. We aren’t born into the world with an instinctive grasp of what things like male and female, hero and victim, or right and wrong are. We learn what these things are from the options available, and the options available are only as numerous as the representations we see in the media. Blade Runner’s options are all pretty terrible unless you’re Ryan Gosling.

Anyway, this is a music website, not a film website. Tonight I’m here to see St. Vincent. Everybody who skipped the last four paragraphs, hello, nice to have you back. Normally when I’m reviewing a gig I bring a notepad with me so that I don’t forget things, but today I’ve accidentally brought the big one I use for work rather than the inconspicuous one I use at gigs, so I’m going to have to resign myself to looking look like the nerdiest St. Vincent fan in the house. Which isn’t hard – Annie Clark is something of a style icon, and there are a lot of stylish people about. None of them have thought to accessorise with a massive notepad though, so maybe I’m the style icon here.

The lights go down at 8PM and the opening act begins – sorry I am aware this isn’t a film review website, but it looks like another film review is coming up – rather than a band opening for St. Vincent, we’re treated to a screening of The Birthday Party, a short film co-written and directed by Annie Clark.

The film depicts a woman on the day of her daughter’s birthday party, who, finding her husband dead, decides to try to pretend everything is fine rather than ruin the party. She stuffs him into a cupboard while she works out what to do. Meanwhile her daughter bounces round the house in a ghost costume (“I am a dead girl!” she proclaims proudly) and the mother tries to keep up appearances, eventually hiding the husband inside a panda costume. It’s all very dark, and very funny in a very Annie Clark way. This isn’t the first time she’s depicted this kind of struggle to deal with the expectations of domestic suburban life – in the video for her 2011 song ‘Cruel’, she is kidnapped by a father, son and daughter, and made to carry out household tasks. She doesn’t perform up to standard, so they bury her alive. Both films seem to consider anxiety around the kind of ‘ubiquitous value system’ she told Pitchfork she doesn’t relate to. It’s a long way from the kind of mythology Blade Runner constructs. The most prominent male character in The Birthday party is dead (the delivery boy who provides the panda suit comes a close second) and the mother spends the whole film trying not to talk about him. Not that it’s a fight between the two films. I just have Blade Runner on the brain, and the difference is striking. I’ll try to stay on topic.

Alright now we have some music. Apologies to the editors for it taking me this long. The curtains part very slightly, and Annie Clark steps out into a beam of white light. To my joy, she opens with 2007 song ‘Marry Me’. I wondered what the ratio of old music to new music would be – her new album MASSEDUCTION is quite different to the albums that came before it. The most interesting review of it I’ve read, by Sasha Geffen, has described the album as “daring to imagine glam rock without men” –

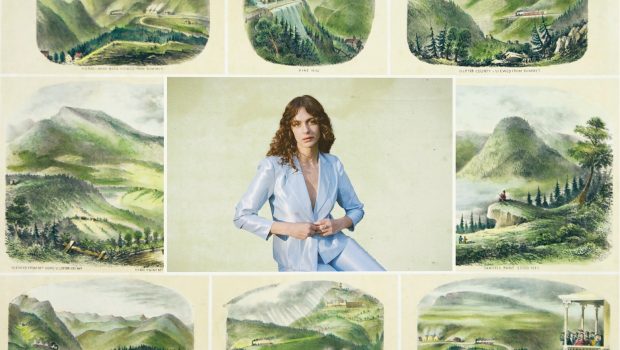

‘St. Vincent barely seems to acknowledge the existence of men at all in her new work. […] Clark’s look echoes the look of men who knew they were breaching the boundaries of accepted masculinity, but she presents resolutely femme, in dresses and a straightened bob and lipstick. It is almost an impossible look: to be a woman in high femme and gaze into the camera as though you are getting away with something.’

In keeping with the high femme, tonight she is dressed in a pink leotard, thigh-high pink stilettos and pink fluffy armbands, with one of her Music Man St Vincent Signature guitars round her neck. I’m a little surprised to see she is performing without a band – just her, her guitar, and a backing track. But it definitely works – she is completely engaging. The lyrics to ‘Marry Me’ – “Oh, John, come on/we’ll do what married people do/let’s do what Mary and Joseph did/without the kid” – taking on a particular irony straight after seeing The Birthday Party. She follows this with ‘Now, Now’, which happens to be my favourite St. Vincent song. I’d spent a large chunk of time the previous week trying to learn the complex guitar harmonics riff that drives the song. She’s playing it effortlessly, and finishes the song with a shredding guitar solo. Inspirational.

The rest of the first half is all music from before MASSEDUCTION. Watching ‘Cruel’, I feel like a lot of this old stuff has a very different feel to how they are on record, or other performances I’ve seen of the songs, which I can’t quite put into words. But then I remember a tweet I saw earlier this week – “#MASSEDUCTION is a good album because it’s made specifically for people whose emotions only alternate between being horny and wanting to die”. There’s definitely some of these two emotions in these performance. The themes of MASSEDUCTION, which are broadly pretty raunchy, seem to have spilled over into the rest of the performance. When she starts ‘Strange Mercy’, a woman next to me shouts, “GO ON, CHICK”, to the amusement of the surrounding audience. I briefly consider writing something glib and obvious about everybody filming ‘Digital Witness’ on their phones, a song about the contemporary urge to film and record everything online – “Digital witnesses/What’s the point of even sleeping?/If I can’t show it, if you can’t see me/What’s the point of doing anything?” – but then realise I’m about to write this on a massive notepad so I can tell people about it online later, so who’s the real dickhead here? Reader, I am the dickhead.

There’s now what seems to be an interval. A woman next to me wearing a Bad Seeds t-shirt tells me the show is in two acts – the first with old material, the second the whole of MASSEDUCTION, which clears things up. We talk about the recent Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds gig in Manchester for a bit. I wonder what the overlap is between Nick Cave fans and St. Vincent fans – Annie Clark took the name for St. Vincent from a Nick Cave song, and I suddenly clock that The Birthday Party was the name of Nick Cave’s band before The Bad Seeds. It’s all coming together isn’t it. Nick Cave is another artist who has created a kind of big mythology around him (intentionally or not), a kind of pseudo-Christian mythology, with Cave himself as some kind of weird prophet as I wrote about last month for Silent Radio. Maybe this is their secret.

Act Two – MASSEDUCTION time. Annie Clark is now wearing a silver dress and standing on a large, square podium. I wasn’t hugely into MASSEDUCTION on record, but live I feel much more into it – something about the production (maybe it’s Jack Antonoff’s influence) wasn’t getting to me through my headphones, but live, feeling the bass through my whole body, the album is an expansive, immersive experience. Video footage is projected onto the back of the stage during performances – for the singles, the music video, but for others, footage that appears to have been made exclusively for the live show. During track two, ‘Pills’, a time-lapse video from the filming of the Facebook promo shots for her new album are projected onto the back of the stage. St. Vincent sits in an interview chair on a film set, in front of a green screen. She is flanked by two women, one holding a boom mic and one holding a clapper board, who are both wearing a black balaclava, a sheer black dress with the breasts cut out, and black crosses taped on their nipples.

The videos are shortcut answers to questions St. Vincent gets asked all the time – “Insert question about what she has been reading lately”; “Insert question about the inspiration behind this record”; “Insert question about what it’s like being a woman in music”. The answers (scripted by Carrie Brownstein of Portlandia and Sleater-Kinney fame) are very St. Vincent. For example, her answer to the question about being a woman in music is “very good question”, while the camera cuts to her nails, which have the words “fuck off” written on them. Elsewhere, she’s said ‘The funny thing for me about it is, it’s always such a non-question. The question is—well, there is no question. The statement is, “You’re a woman.”’

When the BBC interviewed her as promo for this album, this happened to the reporter:

[St. Vincent] sips a drink through a bendy straw that’s been moulded into the word “No”. “That’s in case there’s a yes or no question. We can just save time.”

I think that is another thing that sets MASSEDUCTION apart from the rest of St. Vincent’s output – it’s very direct, it feels more like she’s saying exactly what’s on her mind at any given moment; the layers of irony and confuscation on, for example, the album Marry Me are gone. Not that this is a bad thing, although it does make for a different listening experience. And the immediacy carries live, with St. Vincent on her own, apart from the stage technicians who walk on, often to swap over her guitars (she seems to have a version of her signature guitar in every colour). It feels like a real straight-to-the point transmission of these direct feelings.

Before the title track ‘MASSEDUCTION’, she tells the audience, “I can’t turn off what turns me on’ (a phrase she has said may well be ‘the thesis for the album’) ‘…and I suspect neither can you”. The visuals for the album have a very particular aesthetic (the effect of Alex da Corte, who directed the ‘New York’ and ‘Los Ageless’ videos, is very clear): glaring pastel colours, St. Vincent staring into the camera usually looking a little bit bored and a little bit annoyed, and various strange objects and situations. In ‘Los Ageless’, a bright blue answering machine, an electric nail dryer, a pink hair salon, a telephone made of cake, a yoga studio, slowly wobbling sea sponges on trays; in ‘New York’, St. Vincent in a luminous window, St. Vincent sitting on a pastel purple couch, St. Vincent in some kind of technicolour shopping aisle, St. Vincent spinning a black cube twice as tall as her with a pair of pink-tighted legs coming out of the other side. A lot of the objects remind me of the mother from The Birthday Party (film, not band), and the kind of objects she might encounter in her day-to-day life, and a lot of the framing reminds me of the kind of thing you might see on a huge billboard advertising a high-end clothing company. It’s a marked departure from the kind of aesthetics going on in a lot of St. Vincent’s previous records.

St. Vincent, the self-titled album before MASSEDUCTION, had a similar and similarly surreal look. But before that, her videos were a lot more naturalistic, and a lot of them had a thread in common – like in ‘Cruel’, they tend to show St. Vincent finding herself faced with a group of normal-looking people, and it’s not exactly a comfortable situation. In ‘Marrow’, she walks down a highway, encountering various groups of ‘normal’ people and singing “help me” to each of them, who follow her zombie-like, until in the end she turns to stare them down and they disappear; in ‘Actor Out Of Work’, she faces a group of actors in an audition, staring them down while she sings and they show her their most emotive acting moves; in ‘Cheerleader’, she appears as a giant version of herself chained up in an art gallery, surrounded by art gallery attendees staring up at her. By the end of the song, she breaks free of the chains, moving extremely slowly, but disintegrates and crumbles in the process. They all show situations in which St. Vincent is ‘feeling a little bit alien’. If there’s one big difference on this new album, for me it’s that the anxiety around this is gone – as she said, she’s reinventing the value system this time rather than looking sideways at the existing one.

After ‘Young Lover’, St. Vincent tells the audience “we’re living in totally insane times and everybody knows it”, a statement I am fully on board with after watching MASSEDUCTION live. St. Vincent’s big mythology for this record is, appropriately, aeons away from conventional mainstream culture and after Blade Runner last night it’s refreshing to see a show that uses its imagination as to how things could be. Not that this is anything new. My housemate Hannah Ross pointed out the high femme/hot pink/glossy similarities here with e.g. Nicki Minaj and so many artists that came before her. What is new here is, as Sarah Geffen pointed out, the reworking of a glam rock genre usually dominated by men, that has been pretty much dormant in mainstream culture for a long time. Which is exactly what happened with Blade Runner – the writers of Blade Runner 2049 had thirty-five years to come up with a way to write a sequel which didn’t just rehash the gender issues of the first one, and ended up just repeating the same misogynistic cliches we see in so much popular culture without having anything meaningful to say about it. And with such a wide range of alternative approaches to these kinds of issues (of which St. Vincent represents only one) there’s really no excuse not to do better. I look forward to seeing where mass culture is at when the real 2049 comes around.